The Tower of Babel

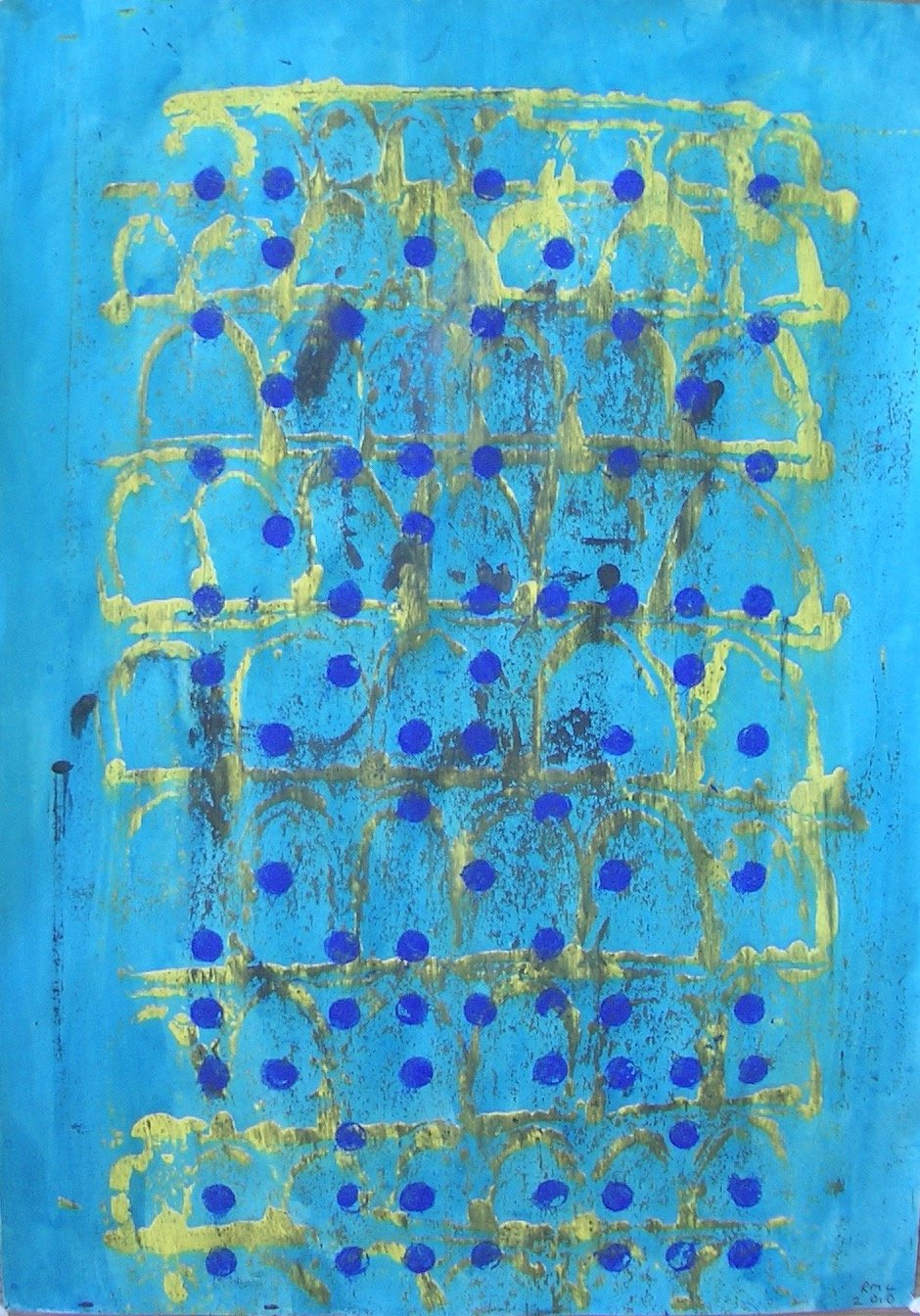

Tower 12 by Rupert Loydell

In the summer of 2010 I found myself collecting and downloading reproductions of works of art that referenced the Tower of Babel which I pasted into a new sketchbook. These included well-known pictures such as those by Gustave Doré and Bruegel as well as more contemporary sculptures and paintings that I found relevant to the topic, including many tarot cards of ‘the tower’, along with photographic details of brickwork and holes in buildings from around the world. Also, in a not uncommon act of synchronicity, my mother produced my copy of The Children’s Bible, which I had not seen since the 1970s. This contains a memorable picture of the tower under construction amongst building site rubble and labour.

By the end of the summer, I had painted a series of 12 towers on A1 paper, another 12 ‘Small Towers’, this time around a foot square in format, and a number of studies and sketchbook pages on the same theme. The series, mainly executed in a mixture of oil paint, oil sticks and coloured inks, included towers that were recognisable from the images I had collected but also more abstract grids and patterns, dots and squares in collision with both themselves and free-flowing inks dribbled onto the page.

Tower 2 by Rupert Loydell

Like many artists I spend as much time considering my work, often making studies from it, after the event as before. I draw my own finished work, I think about where it might sit within not only my own output but also how it related to my contemporaries and predecessors. This essay is research after the event, a collation of others’ responses to the topic and also my own retrospective thoughts.

•

In the Bible story (the story also appears elsewhere, for example in apocryphal Biblical texts, several secular histories and in Sumerian stories) the tower is a sign of aspiration, the result of the desire to ascend, to higher oneself, to get to heaven on one’s own. This aspiration becomes self-glorification, egotistical, evidence of pride: heaven is forgotten and the building becomes an end in itself. As such the people are punished by division and dispersal, the confusion of language and the creation of tribes and nationalities. The King James Bible tells it like this:

And the whole earth was of one language, and of one speech. And it came to pass, as they journeyed from the east, that they found a plain in the land of Shinar; and they dwelt there. And they said one to another, Go to, let us make brick, and burn them thoroughly. And they had brick for stone, and slime had they for mortar. And they said, Go to, let us build us a city and a tower, whose top may reach unto heaven; and let us make us a name, lest we be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth. And the Lord came down to see the city and the tower, which the children built. And the Lord said, Behold, the people is one, and they have all one language; and this they begin to do; and now nothing will be restrained from them, which they have imagined to do. Go to, let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another's speech. So the Lord scattered them abroad from thence upon the face of all the earth: and they left off to build the city. Therefore is the name of it called Babel; because the Lord did there confound the language of all the earth: and from thence did the Lord scatter them abroad upon the face of all the earth.

(Genesis 11 1-9)

In this account, the tower is abandoned, not as often thought, destroyed. Ultimately, it falls or stands on its own.

•

In Colin Thompson’s book for children, The Tower to the Sun, the tower is built to get above the smog that blankets contemporary society, to literally enable a nostalgic rich old man to ‘see the light’ one more time. The tower is assembled from the bric-a-brac and debris of contemporary civilization, including whole buildings. The construction takes many years, and is successful in reaching the sunshine. There is no fall or come down, instead, once the old man has been carried down to bed after sitting in the sun for the first time in many years, ‘an endless line of people climbed the tower until every man, woman and child on earth had seen the sun. One by one they gazed in silence at the light that had given them life.’ At the end of the book the tower stands as a memorial to them, people who have overcome the affliction imposed on them by previous generations; and a reminder of how light underpins the world.

Tower 4 by Rupert Loydell

News from Babel’s first LP, Work Resumed on the Tower, sees the possibility of continuing the building as a metaphor for a successful socialist society, a ‘year in which / Peace spoke to Power / & Peace prevailed’, where ‘the voice of Reason / stayed the hand / of War’. Society is silenced by Babel, which in one song here is synonymous with Auschwitz: the ambiguity of power and language is removed by society’s inability to understand or articulate itself. Silence, however, can be put to good use, for it underpins ‘The year … / no act of violent / will prevail, no order / find its tongue’. Confusion and babble produce miscommunication and then silence; the loss of power and a chance to contemplate and then rebuild both the tower and society:

This was the year

of Peace &

Pause,

The year

of Silence.

•

The tower is a recurring artistic motif. Naïve artists make raggedy structures that make us look up, be it the skeletal Watts Towers in California or Howard Finster’s circular bike sculpture and it’s nearby lo-fi DIY cathedral in his Paradise Garden in Georgia. We might link them to the mystically charged natural sandstone tower of Ayers Rock [Uluru as it is more properly called] in Australia, held sacred by the Anangu tribe, or the fictional mountain which the UFOs land on in Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Each site is considered holy ground, chosen land fit for religious or quasi-religious purpose. Man ascends, gods (or aliens) descend, the two meet half way, caught between heaven and earth.

•

In our day and age towers continue to be a sign of power, just as it was in Renaissance San Gimignano in Italy. Who has the biggest tower? Mine is bigger than yours. As I write I have just returned from London, where The Shard has just become the tallest tower in London. From south of the Thames it takes on other contemporary show-off blocks such as The Gherkin, Canary Wharf and the Lloyds building, as well as more established and familiar skyline features such as St Pauls and the Post Office tower.

But what goes up must come down:

NEW PLACES TO GO

Babel falling slowly

Tower struck down

in a flash of anger

Angst

Amaze me more

Take care when building idols

Images fall daily

The tower rebuilt

Struck out for heaven

Sky silhouette

Strange totems of confusion

longing

Hopes

tumble to the ground

•

This idea of ‘the tower struck down’, permeates our memories of the story, although the Bible God does not strike it down. In the tarot pack, which I am fascinated by on artistic not divinatory grounds, the tower card is said to be ‘the Tarot’s way of acknowledging that the rapid transformation occuring in your world is due to forces beyond your control’ and that ‘change all around you is more likely to be of the permanent kind’. But it also represents a kind of epiphany or revelation, ‘a sudden, momentary glimpse of truth, a flash of inspiration that breaks down structures of ignorance and false reasoning’. The false aspirations, human attempts to reach heaven, are left behind; the metaphorical tower of truth, not the physical one, must now be built.

•

I cannot discuss the tower struck down, nor read explanations of the Tower card such as this without thinking of 9/11:

The Tower shows a tall tower pitched atop a craggy mountain. Lightning strikes and flames burst from the building’s windows. People are seem to be leaping from the tower in desperation, wanting to flee such destruction and turmoil.

Whatever one’s political inclinations, whether one is inclined - as I am – towards conspiracy theories and political intrigues, or not, the image remains. On the day itself I was taking my three-year-old daughter to the park. As we arrived and parked the car radio announced that there were reports of a light plane hitting the World Trade Centre; by the time we came out a couple of hours later the story had changed and we drove home to find the neighbours and my partner in our lounge watching events unfold live in Manhattan. The crashing plane and resulting fire, the jumpers and the collapsing tower, with various shocked voiceovers and pronouncements were then played on what seemed an endless loop until the early hours of the next morning when we went to bed, exhausted and confused.

Tower 5 by Rupert Loydell

Strangely, much of the footage did not get shown again until several months later. (I remember seeing it next when included in an end-of-year round up.) The newspapers of the following morning, which I have kept, show scenes of devastation and destruction that are as beautiful and strange as any fantasy or surrealist film: fire and smoke filter the actual and reflected light over the abandoned grid of the city in a glorious kaleidoscope of oranges, silver, browns and watery greys.

IN REAL TIME

Such beautiful images

with the volume down:

slow motion fireballs,

dust fountains, towers

collapsing in the sun;

replay after replay.

Under the wreckage

where the bodies lie

mobile telephones ring,

needing answers and

wanting the truth

about life and death.

Soldiers and reporters

seek answers in black boxes.

I cannot understand

the dark heart of man,

or see through the smoke

of violence and loss.

A plane is flying

across the screen,

a prayer is rising

through my tears:

lead us from ruin

into light.

Of course, one is not supposed to discuss 9/11 in visual terms, let alone mention the word ‘beauty’, and people such as the composer Stockhausen, who did, were castigated for doing so. But as time passes it is clear that the event remains for most people a visual media spectacle which is surely what it was designed to be? Stockhausen called it ‘the biggest work of art there has ever been’. Slowly the taboo surrounding it is disappearing: novels have been written, paintings have been made; only sometimes does somebody overstep some invisible line of taste. Why, for instance, was composer Steve Reich not allowed to wrap his 2011 Kronos Quartet CD WTC 9/11 in the photograph that he first selected?

Tower 8 by Rupert Loydell

The memories of that day would continue to surface. This is part of a poem initially written in a writing workshop the following year, listening the music of Purple Trap, a noisy improvising jazz group from Japan:

I have seen sunrise

over the glass horizon

of the city, but now

the plane behind my eyes

flies out of the sun again

and into the fortieth floor.

I want to interview and question

the missing and the dead,

talk to people I don’t know.

A man cries into the camera.

The music playing now

is the sound he cannot make:

shrapnel tongue singing

and guitar slam harmonics,

funeral drums and feedback;

the long note of a jumbo jet

falling from the sky

into memory and despair.

•

Language fails us. Babel is also the place of babble, where language is confounded and divided. Abstraction is a language many fail to understand, refusing to learn or consider. David Stubbs suggests in his book Fear of Music. Why people get Rothko but don’t get Stockhausen that contemporary Western society can cope with abstraction in fine art but not contemporary music.

I’d beg to differ. The market may sponsor and support contemporary fine art (if one was cynical one could say that it had found out how to market and sell it) but the majority of people still engage primarily with the content of a painting, i.e. what it depicts. Rothko, for example, has been mis-sold as ‘spiritual’ art, a depiction of the beyond or the zen mind, all concepts which the artist himself rigorously rejected. Try to discuss the nature of paint or the effect of colour on a viewer and you will not get far. Pictures are what society prefers, just as melody and rhythm, a tune, not texture or tone, is what many listeners prefer in music.

Tower 10 by Rupert Loydell

Those who truly listen or see, who understand how music and art are constructed, are able to hear or consider all types of music or visual art (this does not mean they like it). We do not speak a foreign language overnight, why should we be able to understand vocabularies of music or painting immediately? Over time the babble is seen to contain recognisable structures and patterns, inflections and auditory gestures. We become less confused, more alert to nuances and possibilities. We may be prepared to engage with the extremes of sound poetry, noise bands or conceptual art; whatever society’s creative people choose to present to us next.

•

The grid – says Rosalind Krauss – is one of the fundamental motifs of modernism:

There are two ways in which the grid functions to declare the modernity of modern art. One is spatial; the other is temporal. In the spatial sense, the grid states the autonomy of the realm of art. Flattened, geometricized, ordered, it is antinatural, antimimetic, antireal. It is what art looks like when it turns its back on nature.

[…]

In the temporal dimension, the grid is an emblem of modernity by being just that: the form that is ubiquitous in the art of our century, while appearing nowhere, nowhere at all, in the art of the last one. […] By ‘discovering’ the grid, cubism, de Stijl, Mondrian, Malevich… landed in a place that was out of the reach of everything that went before. Which is to say, they landed in the present, and everything else was declared to be the past.

Now, of course, Krauss’ present, her ‘our century’ is the last century, now the past, and many critics and artists might suggest that art itself has moved on again, whilst others might simply report a different experience. The artist Sean Scully, suggest Joanna Kleinberg and Brett Littman in their essay ‘Change and Horizontals’, ‘reimagines the history of abstraction as an art rooted in experience’.

Sketchbook Tower 3 by Rupert Loydell

Sean Scully declares in the same Drawing Centre catalogue that ‘Nothing is abstract: it’s a self-portrait. A portrait of one’s condition.’ This condition obviously includes geographical location and emotional response. Kleinberg and Littman expound:

After a fateful trip to Fez and Marakesh in 1969 he [Scully] became enthralled with the sensual and tactile appeal of the Moroccan striped textiles, Islamic architecture, and the way that the Mediterranean light reflected off the buildings’ facades. He began exploring the possibilities and limits of grid structures and surface textures through the use of household masking tape, acrylic paint, and ink on the paper. Combining the rigorous structural control of the grid with the expressiveness of color, Scully’s self-described ‘paintings on paper’ are inspired by the profiles, hues, and vistas that he happens upon.

Tower Study by Rupert Loydell

Abstraction is always rooted in the real. The grid is physically present in both architecture and in art, in the array of the city’s reflecting windows, its grid of steel and glass, the stripe of each floor as the eye ascends a building’s exterior. Scully articulates his relationship with cities inhabited and visited. Artists such as Mondrian previously did the same, whilst others such as Ben Nicholson softened and reconfigured the grid into something less rigid and more human, something numinous and weathered. These two painters’ work was recently juxtaposed and reconsidered in a fantastic Courtauld Gallery exhibition, Mondrian||Nicholson in Parallel, that clearly bewildered as many visitors as it enchanted:

DUST

The lines under the circles,

the shadows and

faint marks of the brush

whisper songs of colour

across the rooms

of curious tourists

come to see

because it’s free

on a Monday morning.

•

The grid of some of my paintings in this series remind me of the abacus, that early [ac]counting machine, with its rows and columns of beads, often brightly coloured in the children’s version sold in the West. As children we use it to make patterns and sounds; I didn’t have one, instead I played with coloured clothes pegs on the fireguard in our dining room.

My painted grids of dots and lines regulate the pourings and gestural marks my towers are constructed with, impose an order and structure. They also remind me that these are two-dimensional works, which are not about creating illusions of space, height or depth. They are about pattern and colour, mark making and form.

•

As is often the case, I work in isolation, drawing on what I know, assuming that I am somehow doing something different. Later, one comes across others doing similar things, and persuades oneself that this is affirmation rather than discouragement. In this case, having finished my paintings, with all of them pinned up in the studio, a visit to Marcus Campbell Books in London resulted in a secondhand catalogue of work by Steven Foy, who appeared to be painting similar looking canvasses. Today, reconsidering Foy’s images, it is hard to see much relationship between his and my work, just as my final tower painting, faint windows on blue, no longer recalls the silkscreen back of News from Babel’s Work Resumed on the Tower LP, which I originally thought it did (and worried about).

Sketchbook Tower 2 by Rupert Loydell

It is more that the Tower of Babel still seems to be part of meta-narratives that still survive, despite theoretical arguments that they do not. The building of the tower and the dispersal and division of its builders still seems relevant and interesting, still surfaces in songs, paintings, music and art. I’m happy to add to that body of work, to resume work on the tower.

•

Let me finish with part of a favourite song, Peter Hammill’s ‘The Tower’, which was present early on in the making of these paintings. (In fact, I pasted the lyrics into my research sketchbook.):

So: onto the familiar top steps!

In cloud-scud moonlight glow

the Tower reels.

I, the blind man,

feeling for a path I know...

[…]

all around is the humming

of the World.

Too late! With my balance gone,

dead-eyed doll,

I'm falling, falling

back to where I began....

WORKS CITED

Steven Foy, Isolation (London: Steven Foy & Rosie Eaglen, 2003)

Peter Hammill, ‘The Tower’, on Chameleon in the Shadow of the Night (Chrysalis Records, 1973)

Joanne Kleinberg and Brett Littman, Sean Scully. Change and Horizontals (New York: The Drawing Centre, 2012)

Rosalind E. Krauss, The originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths (Cambridge: MIT, 1996)

Mondrian||Nicholson in Parallel, The Courtauld Gallery, 2012

News from Babel, Work Resumed on the Tower (Ré Records, 1984)

David Stubbs, Fear of Music (Winchester: Zero Books, 2008)

Colin Thompson, The Tower of the Sun (London: Red Fox, 1996)

Emily Witt, ‘Steve Reich to change WTC 9/11 album cover’ in The New York Observer, 8/11/11, http://www.observer.com/2011/08/steve-reich-to-change-wtc-911-album-cover/ (accessed 13 April 2012)

The Children’s Bible in Colour (London: Paul Hamlyn, 1964)

‘Tarot Card Meanings’, http://www.biddytarot.com (accessed 26 April 2012)

This essay was first published as part of a box containg postcards, a paperback poetry anthology, and this essay in pamphlet form, by Like This Press. A limited edition in a wooden box also included a small original painting.

Rupert Loydell is Senior Lecturer in the School of Writing and Journalism at Falmouth University, the editor of Stride magazine, and contributing editor to International Times. He is a widely published poet whose most recent poetry books are Dear Mary (Shearsman, 2017) and A Confusion of Marys (Shearsman, 2020). He has edited anthologies for Salt, Shearsman and KFS, written for academic journals such as Punk & Post-Punk (which he is on the editorial board of), New Writing, Revenant, The Journal of Visual Art Practice, Text, Axon, Musicology Research, Short Fiction in Theory and Practice, and contributed to Brian Eno. Oblique Music (Bloomsbury, 2016), Critical Essays on Twin Peaks: The Return (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), Music in Twin Peaks: Listen to the Sounds (Routledge, 2021) and Bodies, Noise and Power in Industrial Music (Palgrave Macmillan, 2022). His paintings were first shown in Northern Young Contemporaries 1985, and since then he has had solo exhibitions in the UK, USA and Russia, and art in numerous group shows.