Femininity, Animism, and Politics: how Pop Surrealists are Re-inventing Surrealism

The Dorothy Circus Gallery is something of a refuge for pop surrealists. Encompassing early proponents of the movement as well as young talent, the gallery startles and delights with visions of mountains with eyes, weird doll-like creatures, bloodied Japanese girls, re-imagined childhoods, ice-cream head people, and other images that are both far removed from and connect with our own reality.

As an art movement, pop surrealism is said to blend the visual vocabulary of lowbrow culture, such as cartoons and street art, with a deep, often fantastical exploration of subconscious and surreal themes. It juxtaposes whimsical or childlike imagery with darker, ambiguous undertones, and offers a critique or satire of modern society's complexities.

Concerned that the contemporary European art scene was predominantly focused on the “tired trajectory of abstract and conceptual art no longer reflective of contemporary sentiment,” Alexandra Mazzanti, together with her mother, Maddalena Di Giacomo, founded the Dorothy Circus Gallery in 2007.

What distinguishes pop surrealism from the surrealisms of the 20th Century?

I think pop surrealists try to be less intellectual, more inclusive, and reach out to a broader audience than their historical counterparts. Hence the “pop.”

Pop surrealism is also a child of globalisation. Our artists come from around the world, and many blend local styles and cultures with the overarching pop surrealism aesthetic.

That overarching aesthetic arguably displays a tendency towards femininity and animism, sweetness and sentimentality, as well as a stance questioning society and politics. However, it is a diverse movement, and there are exceptions.

Boys in the garden by Rafael Silveira, acrylic on canvas, 98 x 85 cm

Like 20th-century surrealism, it speaks to those who don’t stick to reality, who find solace and meaning in sur-reality. It's also a kind of language and attitude towards life. Some people need to look beyond mundane daily life, or they wouldn't survive.

Visible reality is not for everyone!

Do these anxious times feed into the appeal of pop surrealism? Spiralling inequalities, ecological catastrophe, and new technologies have lent a sharp edge to an already absurd political and economic system built on the impossible promise of infinite growth in a finite world. Escaping the realist edifice into a more imaginative space has never felt more attractive.

That imaginative space might be pure fun or it might illumine certain psychological or political truths that ordinary realist diction struggles to articulate.

The hyper-capitalist art market is also absurd. One way to extricate oneself from it is to steer away from the commercial, to avoid the art game, which can often feel hollow and meaningless.

However, the reality is every artist needs to make a living. I think pop surrealists are trying to create a balance between their ethics, ideals, and reaching out to wider audiences, while, at the same time, being meaningful and avoiding the easy sell-out.

Some blue-chip galleries look for artists who can produce loads of very large works very fast. It’s part of the game. The pop surrealists tend to avoid pandering to big money. Instead, they attract a different kind of collector and art lover, not just investors.

Surrealism has roots in radical political ideology. André Breton, for example, was a dedicated communist. Do the new surrealist artists have the same spirit of rebelliousness?

Yes. And there’s another aspect of rebelliousness that has grown since surrealism began in the 20th century: feminism and femininity. Leonora Carrington and a few other notable women artists were “at last” included in the older movements, but not as prominently as men.

In new surrealism, women artists not only predominate; femininity is also inspirational for male artists. Various male artists choose to represent themselves with a female avatar. There is much work around the female figure and a feminine language that can be less rational and more sentimental. It’s often sweeter than older forms of surrealism.

Blooming Muse XVI by Miss Van, 55 x 46cm, oil on canvas

It's also interesting to examine new surrealism’s influence on political street art. In contrast to the masculine and aggressive symbols of struggle and resistance, newer forms of political street art often lean towards dreamlike, visionary, figurative art.

Take Andrew Hem or Seth for instance. Their street art is more romantic, sweeter, and more feminine than the street art from the old school. The dreamlike vision definitely changes the language of rebellion.

All blue by Andrew Hem, 61 x 86.3, acrylic on linen

Pop surrealism is both a continuation of 20th-century surrealism and something new. A stronger tendency or openness to femininity is certainly a distinguishing factor.

It’s also constantly evolving and already changed a lot since the early 21st century. Mark Ryden and Joe Sorren, for example, live in two very different corners of the pop surrealist universe.

Aurora by Mark Ryden, 284 x 147cm, oil on canvas

Ryden invokes a meticulous, hyper-detailed exploration of surreal, otherworldly landscapes that fuse cultural icons, innocence, and unsettling undertones, delving into the subconscious with symbolic imagery that contrasts childhood innocence with themes of death, religion, and consumerism. Rooted in historical, mythological, and esoteric references, Mark Ryden blends classical painting techniques with pop culture symbols to explore deeper themes of spirituality, existentialism, and the commodification of innocence in modern society.

Morning has broken by Joe Sorren, 76 x 100cm, oil on canvas

In contrast, Joe Sorren leans into softer, dreamlike environments, where emotional depth is conveyed through impressionism, abstraction, and subtle improvisation. Sorren's work delves into the nuances of human sentiments and feelings, often exploring memory, nostalgia, and vulnerability. His brushwork and color palettes evoke a deep, almost subconscious connection to the viewer, creating immersive atmospheres that invite reflection and emotional resonance.

While Ryden’s work confronts and provokes, Sorren’s invites the viewer to sink into a quiet, introspective space, making both artists key figures in contemporary surrealism, yet with contrasting approaches to emotional and spiritual exploration.

In the writings of Carl Jung, the anima figure is female for men, and male for females. Can you give an example of a pop surrealist who uses the female avatar? For example, I noticed the predominance of the female figure in the works of Kazuhiro Hori.

Kazuhiro Hori only paints girls. In contrast to the tendency for sweetness that I mentioned, his works are often nightmarish, indeed, one of his first exhibitions was titled “Blood” and featured young girls bleeding and suffering. He represents himself through the torment of female figures.

There is definitely a social critique in his work. Hori explores the pressures and expectations placed on young women in Japanese society. The suffering of these girls reflects the darker aspects of societal norms, especially around gender and innocence.

Empty by Kazuhiro Tori, 50 x 45cm, acrylic on canvas

Kazuki Takamatsu is another Japanese artist who focuses solely on the female figure. Unlike Hori’s raw, nightmarish representations, Takamatsu’s work is ethereal, using 3D depth mapping to create soft, ghost-like female figures that seem to exist in a digital limbo. While both artists center on the female form, Takamatsu evokes a sense of melancholy and loss, as opposed to the outright torment found in Hori's work.

Both choose a female figure to represent their emotions. What they depict is not a model but rather their female avatar, as if they've chosen to express themselves through a woman's voice.

Can you tell me more about animism in pop surrealism?

Christianity effectively buried our native Western animist traditions. Greek, Roman, Celtic and other fairy-tale belief systems used to be widely held; writers in the 16th century wrote about the attributes of fairies, how and why they manifested in certain places. It was considered normal to believe in such things until Christianity repressed these native traditions.

In an age of ecological catastrophe, many Westerners realise that Christianity, which systematically demonises the natural world and creates a god in man’s image, no longer makes sense. The pop surrealist’s fascination with animism reflects a desire to get back under the soil and discover a more fantastic spiritual vision that also values the natural world.

In contrast to Christianity’s view of the natural world as something to be dominated, animism encourages us to see the natural world as alive, sacred, and interconnected.

Animist traditions reflect living forces as opposed to abstract principles of heaven and divinity?

Exactly. Animism is a way of understanding humanity and nature rather than a tool to manipulate and control people.

Yosuke Ueno's vibrant, street-art-inspired gestures layered within surreal compositions invite the viewer into a world where the boundaries between humanity, nature, and the spiritual realm dissolve, creating an imaginative landscape where the vitality of existence pulses through every figure and form, reminding us of the universal rhythm that connects all life.

Flowers by Yosuke Ueno, 53 x 65.5 cm, acrylic on canvas

In Anglo-Saxon culture, big eyes reflected the idea that the memory of these people would last forever. It is a sentimental attitude towards death.

Pop-surrealist animism gives eyes not only to humans but also to mountains, forests, and animals with puppy-like eyes, all of whom are asking to be remembered and cared for.

Ryoko Kaneta paints mountains with eyes, and Joe Sorren’s works often feature pet-like creatures with a soft, emotional undertone, urging us to connect with non-human life.

Mt Fuji Winter Morning by Ryoko Kaneta, 72.7 x 72.7 cm, acrylic on canvas

So, animism is a way of writing sensitivity into the natural world. Some of the more fantastical creatures are also funny and easy to sympathize with.

In Marion Peck’s Still Life with Dralas, the blend of classical still-life composition and whimsical surrealism transforms everyday objects and fruits into animate beings. However, this transformation does not offer a simple, reassuring answer but instead poses a question, inviting a deeper reflection. The title, referencing "dralas" (Tibetan spirits), connects to the animistic theme of the painting, where even inanimate objects seem to possess a subtle, life-like energy.

The traditional still-life setup nods to vanitas paintings, traditionally associated with the fleeting nature of life, yet here, the surreal twist suggests that these objects are quietly observing us—provoking a sense of being watched, rather than offering us clarity.

Still life with dralas by Marion Peck, 35.5 x 45.7 cm, oil on canvas

The sweetness of Peck’s figures may initially charm, but their quiet presence raises deeper questions: What does it mean for inanimate objects to have life-like energy? Are we meant to sympathize with these figures, or are they mirroring our own emotional projections? This duality—between the familiar and the unsettling—captures the very essence of pop surrealism, where the artwork’s meaning unfolds gradually, and its power lies in keeping the dialogue open rather than providing comforting conclusions.

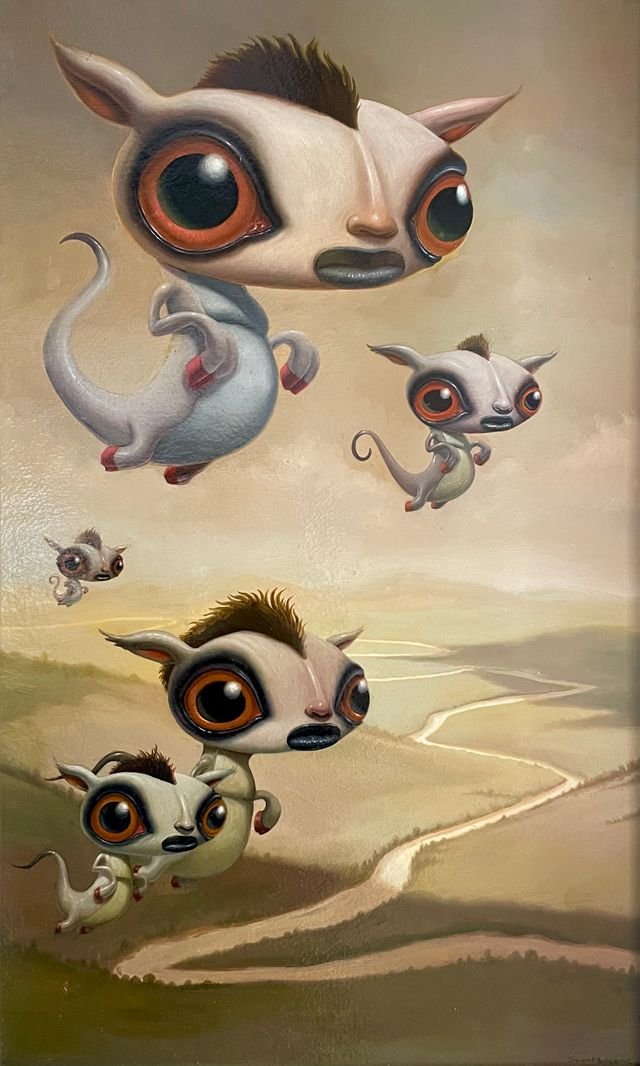

Scott Musgrove often addresses the extinction of animals and environmental issues using creatures with large puppy eyes. While these figures might initially seem cute, their exaggerated features hint at a deeper connection to the themes of loss and vulnerability. In popular culture, the innocent, wide-eyed look is meant to evoke sympathy and concern. However, in Musgrove’s case, this aesthetic serves as a poignant commentary on the fragility of endangered species and the environmental crises threatening their survival. His approach draws attention to the way we sentimentalize animals, while subtly critiquing the superficiality of this sentiment in a world where real creatures face extinction.

Paludosus-Volaticus by Scott Musgrave, 28 x 46cm, oil on board

Among the newer movements, artists have increasingly created what are referred to as “cute creatures.” While this style often stirs sentimental feelings towards non-human life forms, I can’t help but question its deeper purpose. In pop surrealism, the exaggeration of cuteness often holds an underlying mystery, provoking bittersweet reactions and challenging the viewer to think critically. Yet, in some cases, this trend seems to stretch too far—distorting the reality of animals, objectifying them, and overly sweetening their portrayal, which leaves me uneasy.

It’s not that I reject artistic exaggeration, but there's a growing disconnect from the genuine beauty and complexity of real animal world. The tendency to present everything in cheerful pastels and soft, rubber-like forms creates a dissonance, especially when actual animals are facing extinction. Instead of engaging with this uncomfortable reality, the art risks drifting toward an idealized, overly cute version of nature. This shift not only softens the gravity of the ecological crisis but also raises the question of whether it is a distraction from the urgent truths we need to confront.