A labyrinth due for demolition

The mythic Labyrinth was built by Daedalus to house the Minotaur. There is also the 1985 film with David Bowie and Jennifer Connelly scripted by the late Python Terry Jones. In the plural, one may recall Labyrinths, a book by Borges.

One also thinks of the hedge maze in The Shining (Kubrick, not King – the latter was more partial to hedge monsters) through which Jack chases Danny at the climax – the son eludes his murderous father by retracing his steps in the snow, going back to the past to find out the future. Still another hedge maze crops up at the end of Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire – it contains a disguised 'portkey' that transports the hero face to face with his enemy Voldemort.

There is 'The labyrinth of another's being' as spoken of by Yeats. In House of Leaves (concerning, among many other things, a house that keeps on growing and growing), the ostensible original writer Zampano has gone to great lengths to expunge any suggestion of the presence of a Minotaur from his footnote-laden manuscript – every time the topic is raised, the sentence is highlighted in red and struck out.

In his famous schema for Ulysses, Joyce describes the technique of the 'Wandering Rocks' chapter as 'Labyrinth'. It is fitting for a section in which all of Dublin is seen from a god's eye view, intricately crosscutting between the differing characters and vignettes, like ants scuttling through a maze, an episode composed with a map and a stopwatch for maximum accuracy. Yet it is a description that could just as well apply to the entire book, one in which many a reader has lost their bearings, to say nothing of its notorious sequel Finnegans Wake, a dream or nightmare which perhaps warrants the simile even more than its predecessor. Indeed, the very word labyrinth suggests its own adjective – labyrinthine, often used in denigration when describing lengthy novels or unwieldy buildings or impractically complicated plans. Straight lines are preferred, more easily digestible – we do not like the sensation of being lost.

For me, a more personal and immediate labyrinth closer to home is the shed in our back garden. This shed had been habitable once. You could occupy it of a summer afternoon ten long years ago, with ample space at the table where one could read and write and sip one's slowly cooling green tea, the cup continually refilled from the ever-present steaming kettle. The sunlight fell through the open door and the beckoning garden glowed – tendrils of the dancing Russian vine tapped at the window, and chirrups of the birds could be heard, the blackbirds, the sparrows, the wrens and the robins – the latter were the most curious and would look in from time to time. But over the years we looked elsewhere, and so the place went to rot and rack and ruin. It lurked at the back of the mind as something to be dealt with, but there was always something more pressing to attend to and thus we let it slip aside, pretending it did not exist.

Only in lockdown, with time on the hands and an existential crisis brewing, only then was time found to start clearing out our shed, in the hopes perhaps of putting this waste of space to use. Easier said than done. For the wreckage of the shed will come to stand for the wreckage of the owner's mind. This was a labyrinth that no Daedalus built, a labyrinth without a Minotaur – unless it is the spectre of depression or dementia itself, a monster that cannot be slain.

One gingerly inches open the door and at once you are hit with a wave of flies and the scuttle of spiders. The rank odour that emanates offers ample evidence of mice and sundry other rodents having once been in residence. Dust is everywhere and falling leaves peter through the ceiling's cracks and window's chinks. Some areas are waterlogged, owing to leakages in the roof and overall rising damp in the rotting walls. You ease your way inside little by little, your nervous passage held up by the myriad types of debris over which one trips, like the piles and stacks of unreadable and unsellable books with frayed and yellowing pages chewed and torn. The air is fetid and the nose will start to run.

The atmosphere is bad for the lungs – one develops a cough after any length of time in there – a bad sign during times of Covid. An uncle wisely cautioned and reprimanded us for not wearing masks, given the toxic fumes likely emanating from some of the rotting garbage buried within, smeared with the secretions of spiders and slugs and snails and sundry slaters. Indeed, one's nails are always newly grimed and mucky in the aftermath of each ineffectual excavation. No Ariadne's thread will guide thee through this maze – only a slew of spiderwebs to choke and hinder the wary wanderer, rooting through rubbish in search of stuff to save. The slaters crawl and the bees buzz – thank gawd we are in a part of the world that allows no cockroaches.

Mementos of a rich past life are buried under the piles of garbage and miscellaneous crap, but the difference between trash and treasure is difficult if not impossible to disentangle. My old schoolbooks sit side by side alongside my father's own, his boyish handwriting neater than mine ever was. Here be a postcard from a Grecian island, over here lies a crumpled Valentine, and on this ledge sits a letter from a forgotten friend, who no longer resides at this address nor will answer this listed number since it is by now long defunct.

And the books are countless, endless, incalculable, whether bursting out of boxes or fallen on the floor or crazily piled upon the sagging table. Some can be salvaged and saved or sold, but many are hopelessly ruined, caked with muck and filth, fit only for dumping. The sadness is compounded, for these are books the original buyer can no longer read. You can form a map of his past pursuits and interests just by browsing through them – the German books, the chess books, the philosophy books, the travel books – you can even catch glimpses of his past careers in the form of essays from former pupils and photocopied journals containing relevant articles pertaining to his modules. And here be a childish scribble in a familiar hand...

My old doodles! Boxes of illegible juvenilia invite a disgusted and despairing perusal. Incoherent would-be epics and series were started and abandoned time and again. Scores of paper wasted and defiled by my messy scrawls in crayon – seemingly attempting in vain to evoke the shapes of Sonic the Hedgehog and Doctor Robotnik, sometimes Batman, sometimes The Mask. The originals are much in evidence too, faded comic strips crumbling into seeming ash. They are in such rotten condition that no self-respecting collector would be caught dead coughing up for them. The Beano, The Dandy, The Beezer, The Geezer, Buster, you name it, they're all represented. There are also educational aids like Letterland, peopled by Kicking King and Clever Cat. Old newspapers crammed full of old news abound, as do the castoff relics of former housemates, sweet wrappers, discarded prophylactics, snippets of train tickets, stacks of nudie magazines, tins of pens that don't work and stubby pencils badly needing sharpening. One finds also broken lampshades and blown lightbulbs, mouldering carpets and soggy schoolbags, untold Sudoku puzzles and illegible crosswords, faded jigsaws and cheated quizzes.

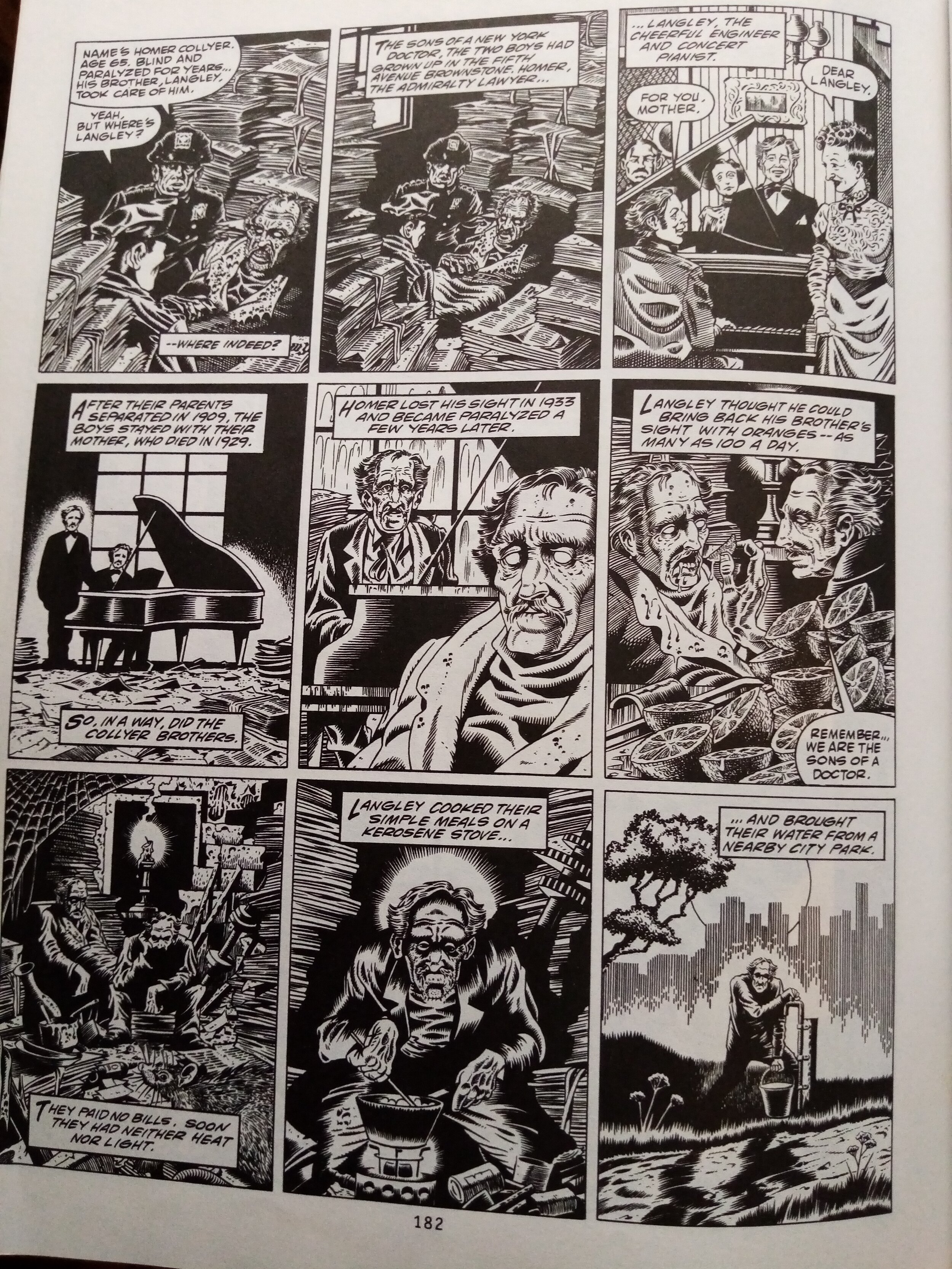

This sad setup, a result of crazy hoarding and a pathological reluctance to dispose of anything, is at times reminiscent of the Collyer brothers, whose very surname echoes our own. I first learned of them in The Big Book Of Weirdos, edited by Gahan Wilson and illustrated by scores of comic book artists. This too was one of the many childhood tomes we unearthed in the progress of our forages that took on the aspect of archaeology – the wet pages stuck together and needing blowdrying to wrench them apart. And there they all are within this rescued book, the so-called 'weirdos', like Howard Hughes and Grigori Rasputin and Nikola Tesla and Edward D. Wood Jr and William Randolph Hearst and Stephen Tennant and Idi Amin and William Lyon Mackenzie King and J. Edgar Hoover and T.E. Lawrence and Edgar Allan Poe and Wilhelm Reich and Adolf Hitler and William S. Burroughs and Andy Warhol and Salvador Dali – all come alive as comic book characters illustrated in beautiful black and white.

But the Collyer brothers were a famous pair of New York eccentrics and recluses who grew up at 2078 Fifth Avenue, the elder an admiralty lawyer, the younger an engineer and concert pianist. Their father died. Their mother died. They stayed on in the property. Elder brother Homer went blind in 1933 and was later paralyzed. His younger brother Langley tried in vain to restore his eyesight with incessant oranges, as many as 100 a day. Langley also started keeping stashes of newspapers for Homer's sake, in the belief that he'd want to 'catch up' on the news the day he could see again. They paid no bills and soon had neither heat nor light. Can one imagine the kind of life they must have led in that crowded darkness? Scared by the scuffles of random intruders, Langley grew defensive, and the corridors of papers became boobytrapped – a strategy which backfired on him in the end, for he was hoisted on his own petard.

On his way to feed Homer one day in 1947, he tripped over one of his own boobytraps and was entombed in trash. The police were alerted by a tipoff, from someone who had noticed that the property was beginning to reek of decaying corpses. It took three weeks to clear 120 tons of refuse from the house, finding, among other things, the dead body of the 65-year old Homer, fourteen grand pianos, most of a model T-Ford, three thousand books, sewing machines, guns and swords, and the rotting remains of the selfsame unfortunate Langley, mauled by rats, lost in his own labyrinth. Their names became proverbial – many a subsequent New York teenager was told to tidy their rooms or else: 'You'll end up like the Collyer brothers'.

The Collyer Brothers. Text by Carl Posey, illustrations by Graham Manley. Pages 182-3 of The Big Book of Weirdos

Skimming the pages of this book, one may also chance upon the tale of Sarah Winchester on pages 176-7, famous daughter-in-law of the famous gunmaker, who built room upon room upon her house, a growing parasitic mass like a kaleidoscope of annexes and addenda, all only to facilitate her preference for sleeping in a different chamber each and every night, the better to escape the phantoms she feared would prey upon her sleeping self come nightfall, all because of a medium's warning, an injunction to build and build and keep on building to keep the ghosts at bay. Her haunted house well warrants the appellative of 'labyrinthine'. She was recently made the hapless subject of a lame jump-scare horror-cum-thriller starring a slumming Helen Mirren – it did lousy business and went rapidly to Netflix.

Sarah Winchester. Text by Carl Posey, illustrations by Batton Lash. Pages 176-7 of The Big Book of Weirdos

But now the book has been duly skimmed and wiped down and laid aside to dry in the sun. It is one of the more fortunate tomes; it has survived its long exile in this dismal shed without disintegrating altogether, the fate of many of its fellows. And in the meantime we continue to sort and comb through the refuse and little by little the shed begins to empty as the weeks and months go by. Soon one can make out forgotten corners of the room that haven’t seen daylight for decades, and soon there is even space enough to swivel about or crane one's neck.

And so we fill our black and bulging bags with old newspapers and magazines and crumpled bits and scraps of paper and hope the bin-man will collect them before a skip and wrecking ball is hired. And maybe one day soon the shed shall at last be empty and fit for repurposing, if only the ghostly revenants can be chased away from within its echoing walls. Perhaps even an inhabitant might breathe some life back into it. For now it stays haunted. A labyrinth due for demolition. We have been lost in it long enough.